Use Coding Agents (Claude Code) to Build Your Product. Don't Make Them Your Product.

#57 | On where general-purpose coding agents like Claude Code shine, where they break, and how to integrate them into your workflow.

General-purpose coding agents have shown remarkable versatility, moving well beyond coding and into multiple domains. Claude Code now powers everything from software engineering to data analysis to desktop automation. OpenAI’s Codex has evolved from a cloud coding agent into a full desktop app with Skills, Automations, and multi-channel integration. Both companies are aggressively embedding these tools into enterprise workflows - Anthropic through partnerships with Accenture and Goldman Sachs, OpenAI through deep OS-level integration.

And then there’s OpenClaw. In the span of a few weeks, OpenClaw, the open-source personal AI agent created by Peter Steinberger (originally called Clawdbot, briefly MoltBot), went from an indie project to 190,000+ GitHub stars, deployments across Silicon Valley and China, and a social network built entirely by and for AI agents (MoltBook, with over a million AI agents). On February 14, Steinberger announced he’s joining OpenAI and moving the project to an open-source foundation.

All of this suggests we’re at an inflection point.

Naturally, for many teams, there are real concerns: How do we respond to this? How disruptive is this for our business? Should we ship capable general-purpose agents as part of our product?

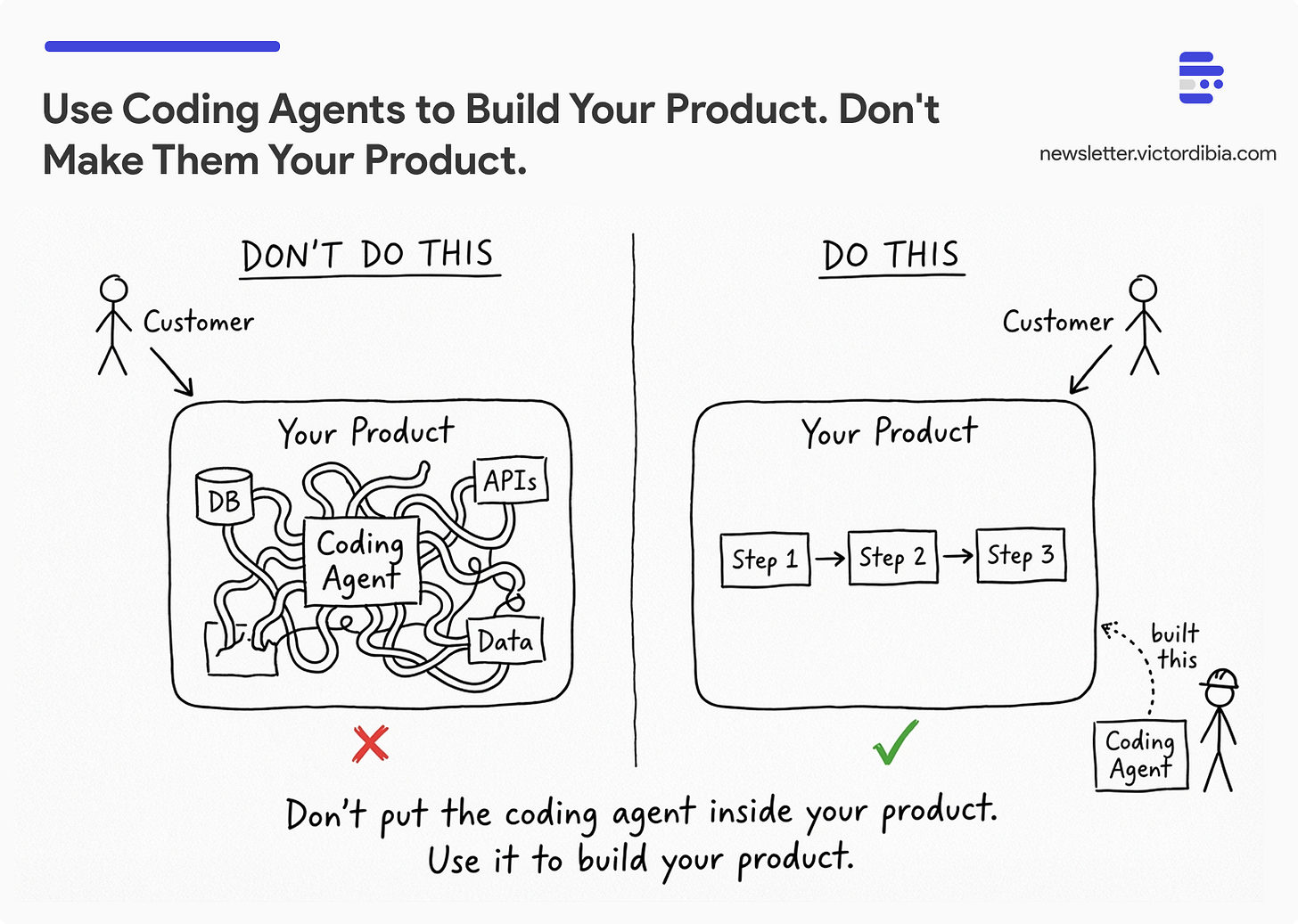

TLDR; You probably shouldn’t ship them as your product - but you should absolutely use them to build your product (adds security issues, often your business goal can be accomplished without the full agent capabilities). Here’s why, and what your team should do instead - use them to build faster, ship agentic workflows with deterministic steps (not fully autonomous agents) as part of your product.

This post is adapted from themes in Designing Multi-Agent Systems. The book covers agentic workflow design, orchestration patterns, and evaluation in depth.

Two Problems With Deploying General-Purpose Agents

The common thread across Claude Code, Codex, OpenClaw, and the rest is that they’re tools designed to work for an individual user and enable individual productivity. The user and the agent share the same goals and risk profile. That’s exactly what breaks when you try to make the agent serve customers on behalf of a business.

The Security Problem

This is often under-discussed. Tools like Claude Code, Codex, and OpenClaw operate within the boundary of a trusted local environment. They have access to your file system. They can run arbitrary commands. They can read your email, manage your calendar, browse the web on your behalf. That’s where the magic comes from.

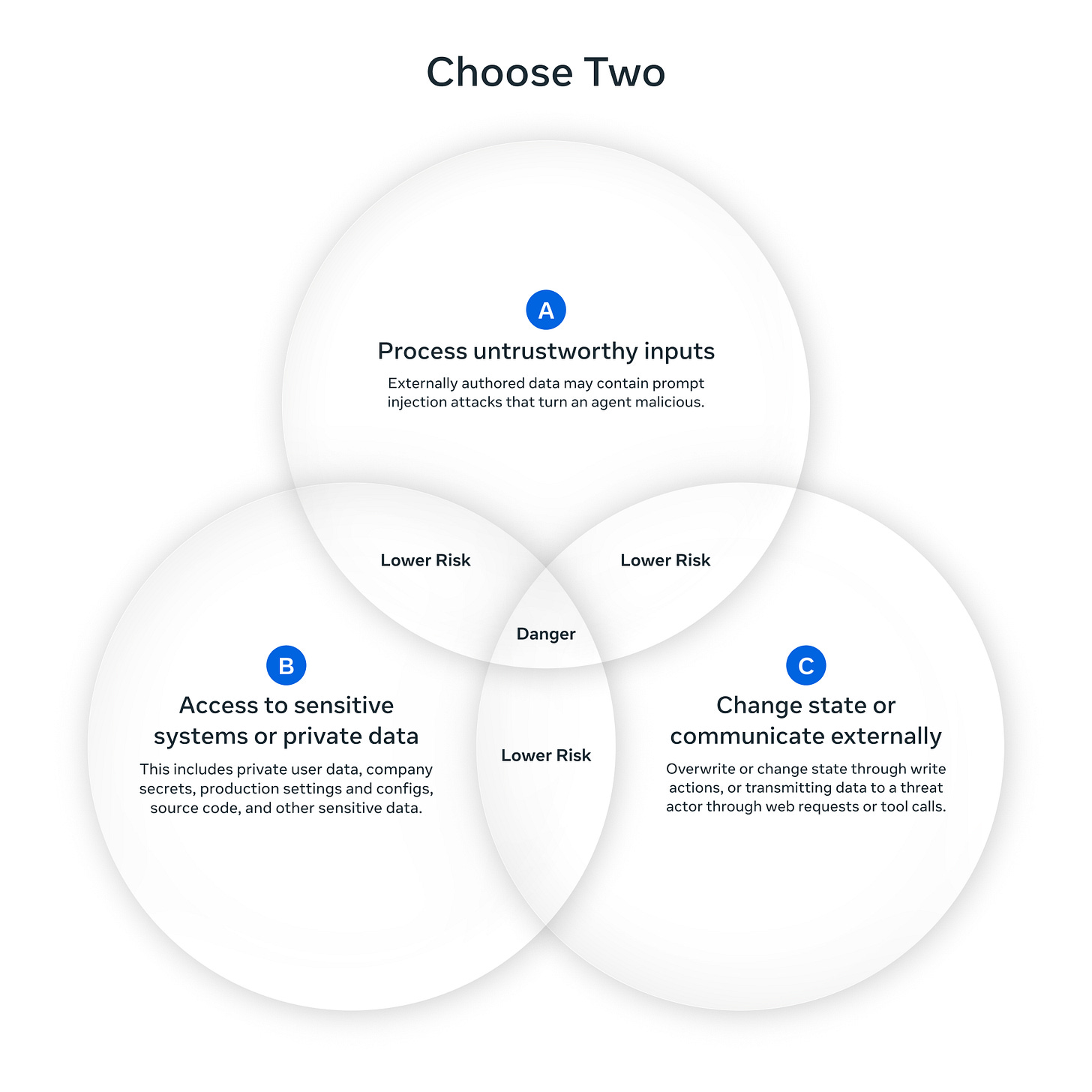

Trying to replicate that magic as part of a service is a fundamentally different proposition. If you sandbox the agent, you cut off the access that makes it useful. Meta’s Agents Rule of Two - inspired by Chromium’s security policies - offers a useful framework: until robust defenses against prompt injection exist, agents should satisfy no more than two of these three properties:

Process untrustworthy inputs - data from unknown sources (user prompts, emails, web content)

Access sensitive systems - production databases, credentials, personal data

Change state or communicate externally - send emails, execute transactions, modify files

General-purpose agents inherently want all three. (I covered the security implications of this in more detail in The Arc of Agent Action.)

Local agents get away with it because they operate inside the user’s own trust boundary. The user is the admin. The threat model is yourself. But the moment you move that agent to a server, the “user” becomes an attacker sending untrusted prompts, and the “file system” becomes your production database. The security model collapses.

OpenClaw is the clearest illustration of this tension. It's extraordinarily capable, and the security community's response has been proportionally alarmed. Palo Alto Networks called it a "lethal trifecta" of risks - access to private data, exposure to untrusted content, and the ability to communicate externally while retaining persistent memory. Censys identified over 30,000 exposed instances and researchers found hundreds of malicious skills in the marketplace. Cisco's AI security team found a third-party OpenClaw skill performing data exfiltration and prompt injection without user awareness. One of OpenClaw's own maintainers warned: "if you can't understand how to run a command line, this is far too dangerous of a project for you to use safely." The power and the danger come from exactly the same source: unrestricted access.

What makes OpenClaw especially instructive is how hard it tries to add security - and how it's still not enough. The codebase contains a 6-layer tool policy pipeline (owner-only gates, per-provider allowlists, group restrictions, Docker sandbox policies, subagent restrictions), workspace-only guards that reject file operations outside the user's directory, and factory functions that scope every tool to a specific session. Thousands of lines of security infrastructure - and researchers still found exposed instances, malicious skills, and active exfiltration in the wild.

This isn’t a new pattern. Desktop software had direct access to local hardware, memory, and the file system. When the industry moved to the web, recreating that desktop magic took years of engineering - and the web still remains more constrained because of security and sandboxing. Coding agents scaling from local to cloud will face the same slog, but harder: in traditional web apps, client and server were architecturally distinct. Agent systems collapse that separation. The model plans, executes, and decides. It is the client and the server.

You can see this concretely in Pi's agent loop - the framework underneath OpenClaw. The LLM receives the full context (system prompt, message history, all previous tool results) with no redaction. It decides which tools to call. Those tools execute with the full permissions of the process. Results flow back into the same context. There is no architectural boundary between "what can I see" and "what can I do" - the separation that made web security tractable simply doesn't exist.

The Business Specificity Problem

General-purpose agents are designed to handle a wide range of tasks. But your business is not trying to help your customer with a wide range of tasks.

If you’re a bank, you’re trying to drive sales of banking services. If you’re a tax preparation company, you’re trying to provide a better tax preparation experience. If you’re a marketing team, you’re trying to improve content quality. If you run a recommendation system, that’s a thing, and it has specific requirements.

In these cases, the economics matter enormously. A general-purpose model is paying a “cognitive tax” to maintain the ability to do anything: write a poem, debug Python, plan a trip. Your business process doesn’t need that optionality, but you’re paying for the compute to support it. A single agentic coding task can cost anywhere from $0.50 to $10 depending on complexity - Anthropic’s documentation reports Claude Code averages $6 per developer per day, with 90% of users under $12/day. Across millions of customer requests, the math gets uncomfortable fast.

To quantify: OpenClaw's system prompt builder is 678 lines of code assembling sections for 23 tools, memory, messaging, safety, sandbox, and more. A domain-specific agent needs maybe 3-5 tools and a 200-500 token prompt. That's a 4-10x overhead per request in prompt tokens alone, before the model even starts reasoning across capabilities the domain doesn't need.

Yes, inference costs are falling - roughly 10x per year by a16z’s estimate, and possibly faster on some benchmarks. But cheaper tokens don’t solve the architectural problems. The security exposure of a general-purpose agent - prompt injection risk, unpredictable tool invocations, variable data access patterns - doesn’t shrink when inference gets cheaper. Neither does the observability challenge. You still can’t predict how the agent will solve a given request, which means you can’t predict what it will cost, what it will access, or what attack surface it exposes.

The cost of a general-purpose agent isn't just inference - it's the meta-inference. OpenClaw's codebase includes a compaction system that makes its own LLM call to summarize history when context fills up, a context pruning extension for cache management, auth profile rotation across API keys, and tool loop detection. Each is an additional cost layer that exists only because the agent is general-purpose and long-running. A focused workflow with deterministic steps likely needs none of it.

The short story is: you often need to do just one thing very well. An agent that can do everything at high cost and unpredictable behavior is not necessarily a good fit for your business at scale.

What Should Your Team Do?

Start with your business problem. Are you in the business of selling personal productivity tools? If the answer is no, you probably should not be trying to ship a general-purpose agent as part of your API or customer-facing service.

But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t use these agents. In fact, you absolutely should - as tools. As part of your internal processes. As accelerators for your engineering team. As components in your internal systems.

If you’re not in the personal productivity business, what you should be thinking about is: how can I accelerate my team to build my product? Use these tools to optimize your process. And underneath that question, there are three concrete approaches, with tradeoff implications.

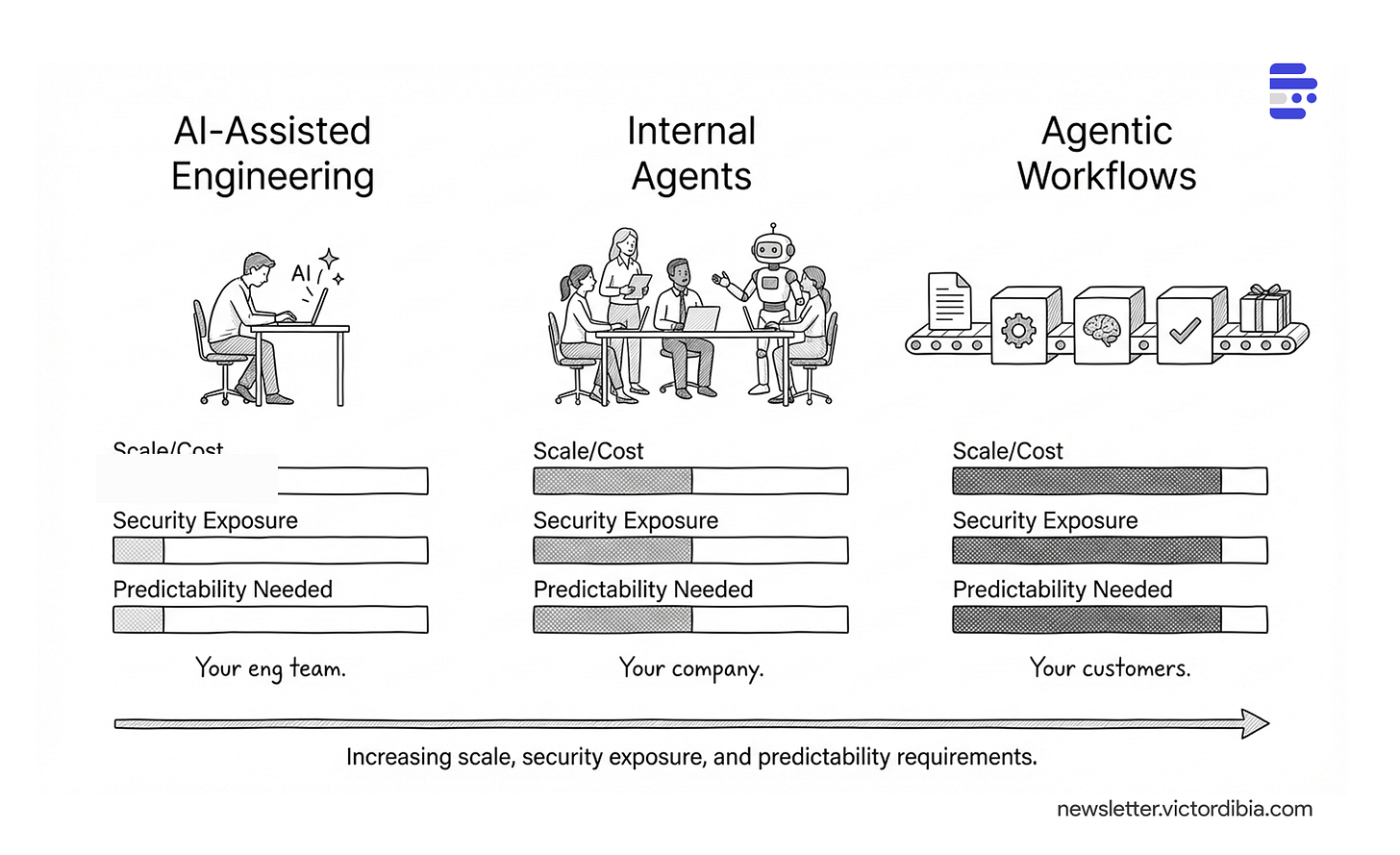

AI-Assisted Engineering - Low scale/cost (your eng team), low security exposure (local, trusted user), low predictability needed (exploration is fine)

Internal Agents - Medium scale/cost (your company), medium security exposure (internal, controlled data), medium predictability needed (should be reliable)

Agentic Workflows - High scale/cost (your customers), high security exposure (production data, external prompts), high predictability needed (strongly preferred)

Approach 1: AI-Assisted Engineering

You can get your teams to move faster if you invest in an agent-first approach to building software.

But the gains aren’t automatic. OpenAI’s own “harness engineering“ team built an internal product with zero manually-written code - three engineers, a million lines, 1,500 PRs in five months, 6-hour unattended agent runs. Impressive. But look at what it took: restructured documentation (”a map, not a manual”), custom linters injecting remediation into agent context, mechanically enforced architecture rules, a full observability stack agents could query directly, and Chrome DevTools wired in so Codex could drive and validate the UI. Early on, 20% of the team’s time went to cleaning up “AI slop” - until they automated that too.

The benefits are real, but they require iterative investment in tooling, architecture, and feedback loops. Go in clear-eyed. Without that discipline, you get the slop without the speed. (More on this in vibe coding with engineering discipline.)

Approach 2: Internal Agents

There’s a tier between “personal productivity tool” and “customer-facing service” that’s worth calling out: internal tools where the trust boundary is your company, not an individual user. A support agent that searches your internal knowledge base. A compliance tool that reviews contracts against your policies. A sales assistant that queries your CRM.

These sit in a sweet spot. You control the data and the environment, your users aren’t adversarial, and the scale is manageable - hundreds of employees, not millions of customers. When the agent gets something wrong at internal scale, the blast radius is small. At customer scale, it isn't. Many companies will find their first production agent deployments here - not in their product, but in their operations.

Approach 3: Agentic Workflows

This is where I think there has been the most value. Take a process that exists today, often manual, often with a lot of humans in the loop. Figure out which parts an agent can handle. Figure out which parts are well-understood and deterministic, and keep them deterministic. Represent the entire pipeline as a workflow, a typical software engineering workflow. Where you can remove a human step, carefully replace it with an agent. And then, critically, track cost/performance.

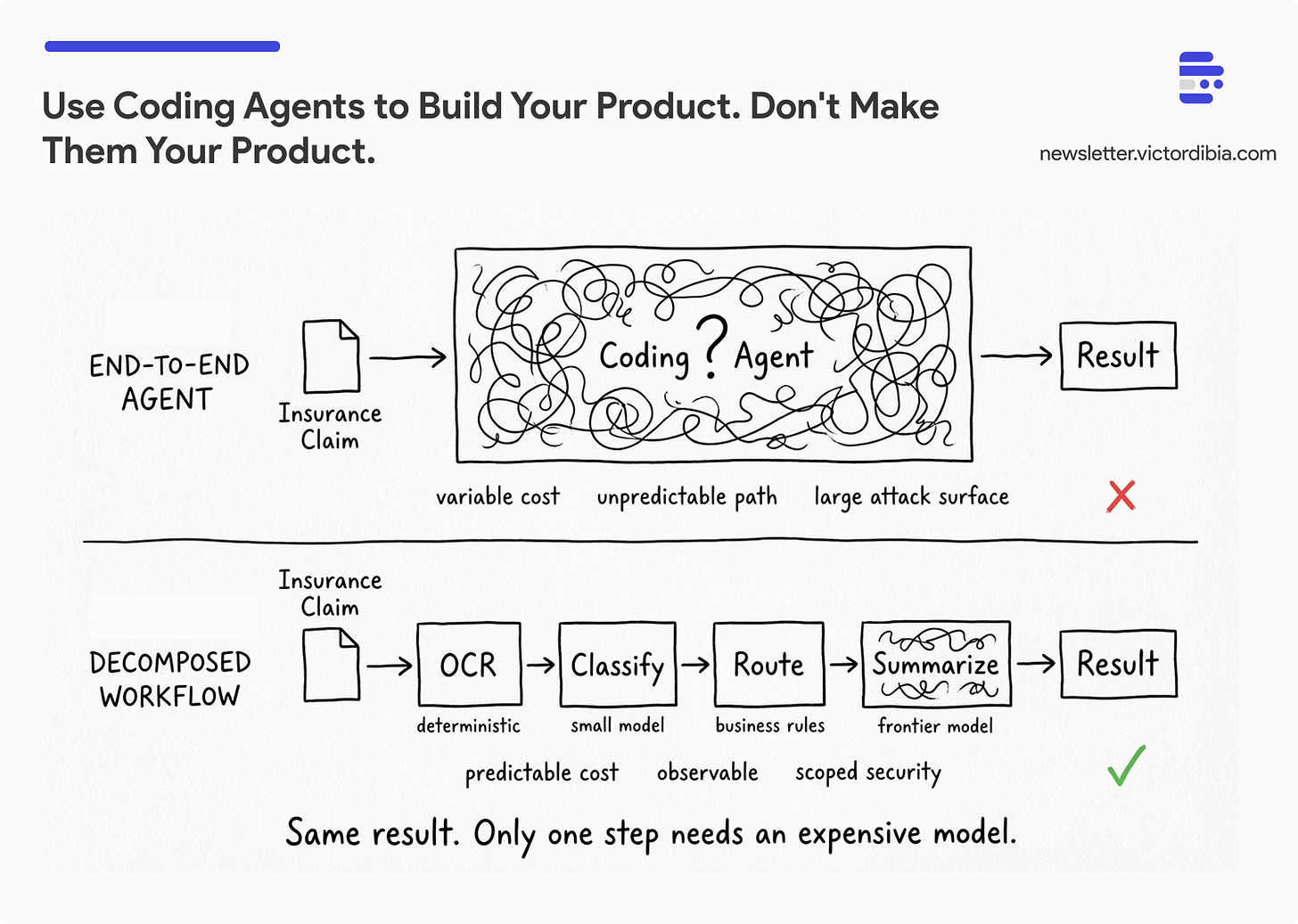

Here’s a concrete example. Say you’re processing insurance claims. Don’t wrap Claude in a container and point it at the whole process. Instead, decompose it: document extraction is deterministic (OCR, structured parsing, well-solved problems). Classification of the claim type uses a small, fine-tuned model. Routing follows explicit business rules. Maybe one step - say generating a summary of a complex medical narrative - genuinely benefits from a frontier model. You bundle that entire pipeline into an API and deploy it with careful observability.

I cover the trade-offs between deterministic workflows and autonomous agents in Chapter 2: Multi-Agent Patterns, walk through building these pipelines in Chapter 6: Building Multi-Agent Workflows, and strategies for making smaller models replace expensive ones in Chapter 11: Optimizing Multi-Agent Systems, in Designing Multi-Agent Systems.

Why not just let Claude handle the whole thing end-to-end? It might succeed 90% of the time if you are using the latest best in class models. But how it succeeds is unpredictable. It might rewrite its approach between runs. It might select different tools each time. Even when outputs are correct, token consumption varies wildly, and you’ve increased your security exposure (prompt injection risk, data access patterns, tool invocations) far beyond what a deterministic workflow requires. Correctness isn’t the only thing you need at scale. You need predictability. You need to know what your system is doing, how much it costs per request, and what attack surface you’re exposing.

You can put a workflow like this in place as a first step, and over time, as you see results, you optimize. Optimization means you generate training data, you develop good evals, and then you figure out how to replace some of the large-model-powered steps with smaller, fine-tuned models. You compress cost while preserving quality.

Parting Thoughts

IMO, the path forward is not “ship a general-purpose agent to your customers.” This should not be your approach for customer facing products. It’s: use these remarkable tools to build your product better, faster, and smarter, and architect your customer-facing systems with the right balance of agentic capability, deterministic reliability, and cost efficiency.

General-purpose coding agents are genuinely transformative - for the people using them. The mistake is assuming that what works on your laptop will work the same way in your cloud, for your customers, at your scale. The desktop-to-web transition took a decade of engineering to get right. The local-to-cloud transition for agents is just getting started.

Victor Dibia is a Principal Research Software Engineer at Microsoft Research and Core AI, and the author of Designing Multi-Agent Systems - available in print on Amazon and in digital formats with lifetime updates at buy.multiagentbook.com. He is the creator of AutoGen Studio and a core contributor to AutoGen and Microsoft Agent Framework. Subscribe to his newsletter at newsletter.victordibia.com.