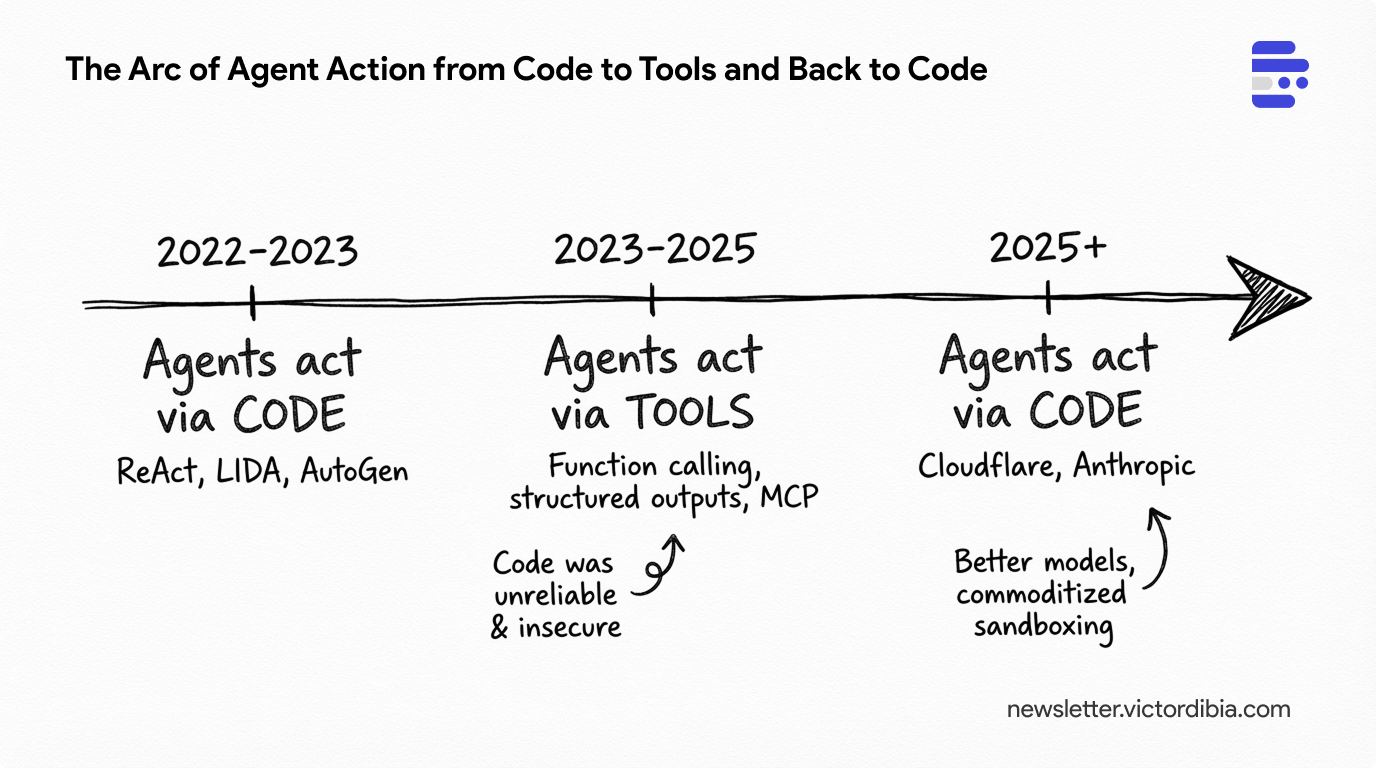

The Arc of Agent Action from Code to Tools and Back to Code - And Why Anthropic's SKILLS.md is Not New

Issue #55 | Early agents (LIDA, AutoGen) supported actions via code. Then the industry moved to action via tools/structured output. And now we are back again to code. What happened?

Anthropic recently introduced Agent Skills [1]—folders containing a SKILLS.md file with instructions, scripts, and resources that agents can discover and load dynamically. The model reads the skill when relevant, executes bundled code, and solves problems using complex control flow rather than chaining discrete tool calls.

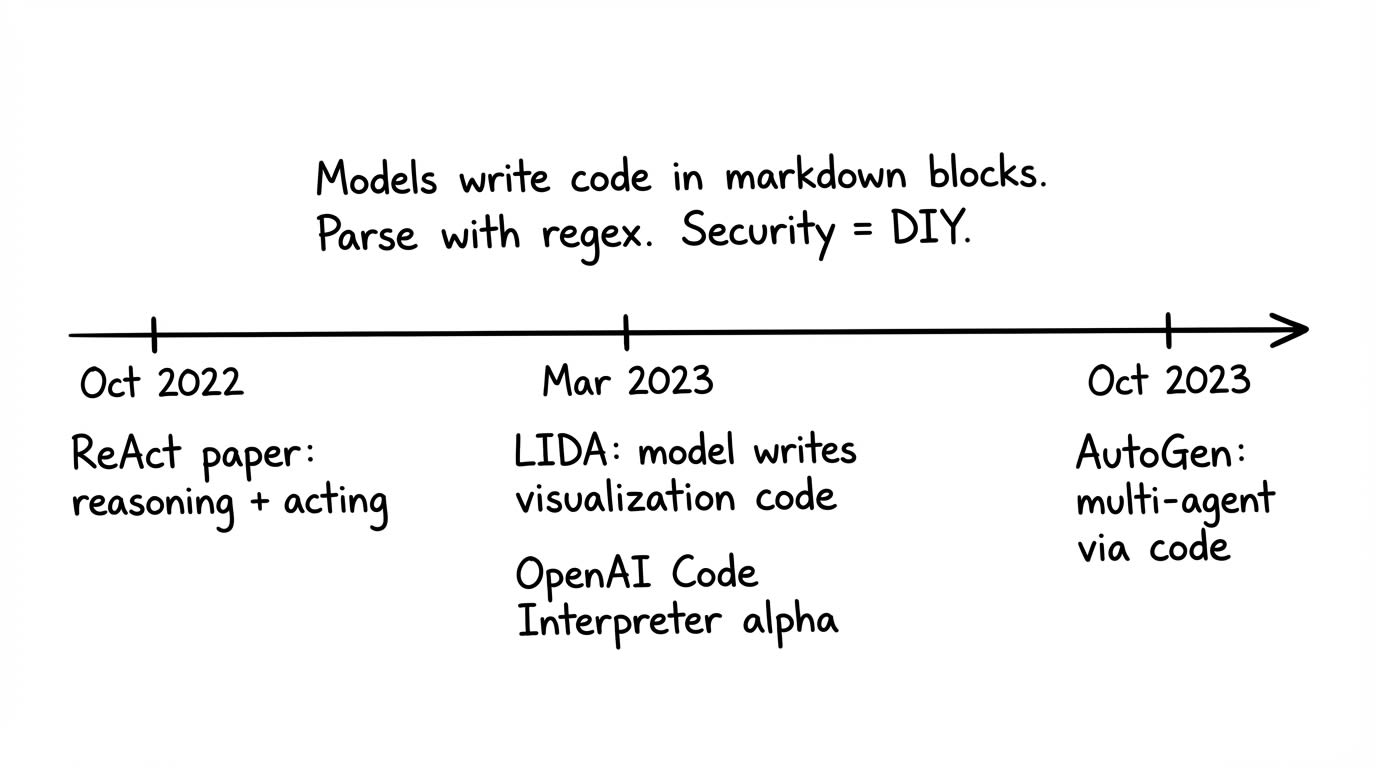

If this sounds familiar, it should. In late 2023, when I was building the first version of AutoGen Studio, this is exactly what we did. Users wrote Python files as skills, we added them to context (full code or just signatures), and the model wrote programs that integrated/orchestrated those skills. At the time, most models were inconsistent in generated structured output (the building blocks for tool calling) but mostly of them could write code fairly well.

Fun fact: One of the first agentic systems work I led at Microsoft in August 2022 (before chatgpt release, before autogen) was LIDA - an agentic workflow for automated data visualization based on code execution. The visualization module worked by generating code (using the Davinci 2 and gpt-3.5-turbo models at the time) which was executed to created visualizations.

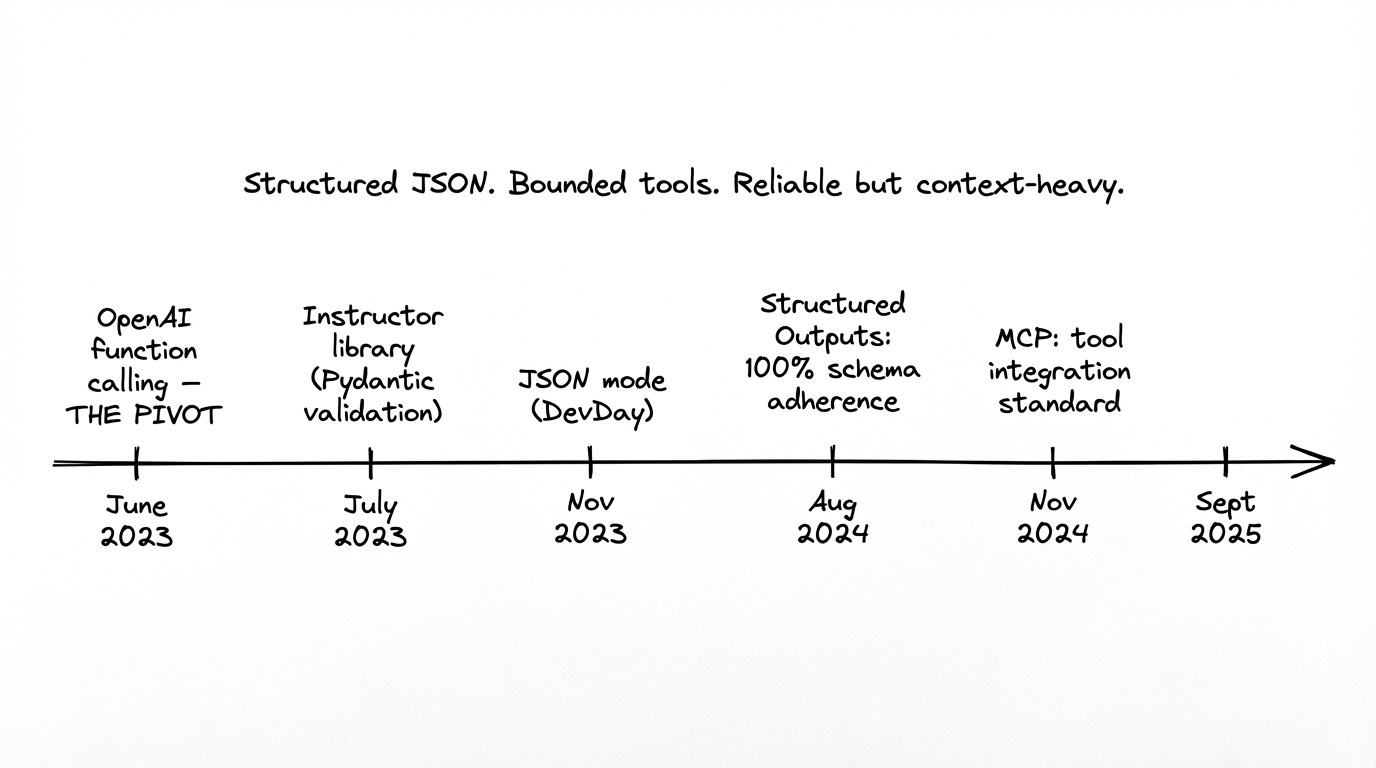

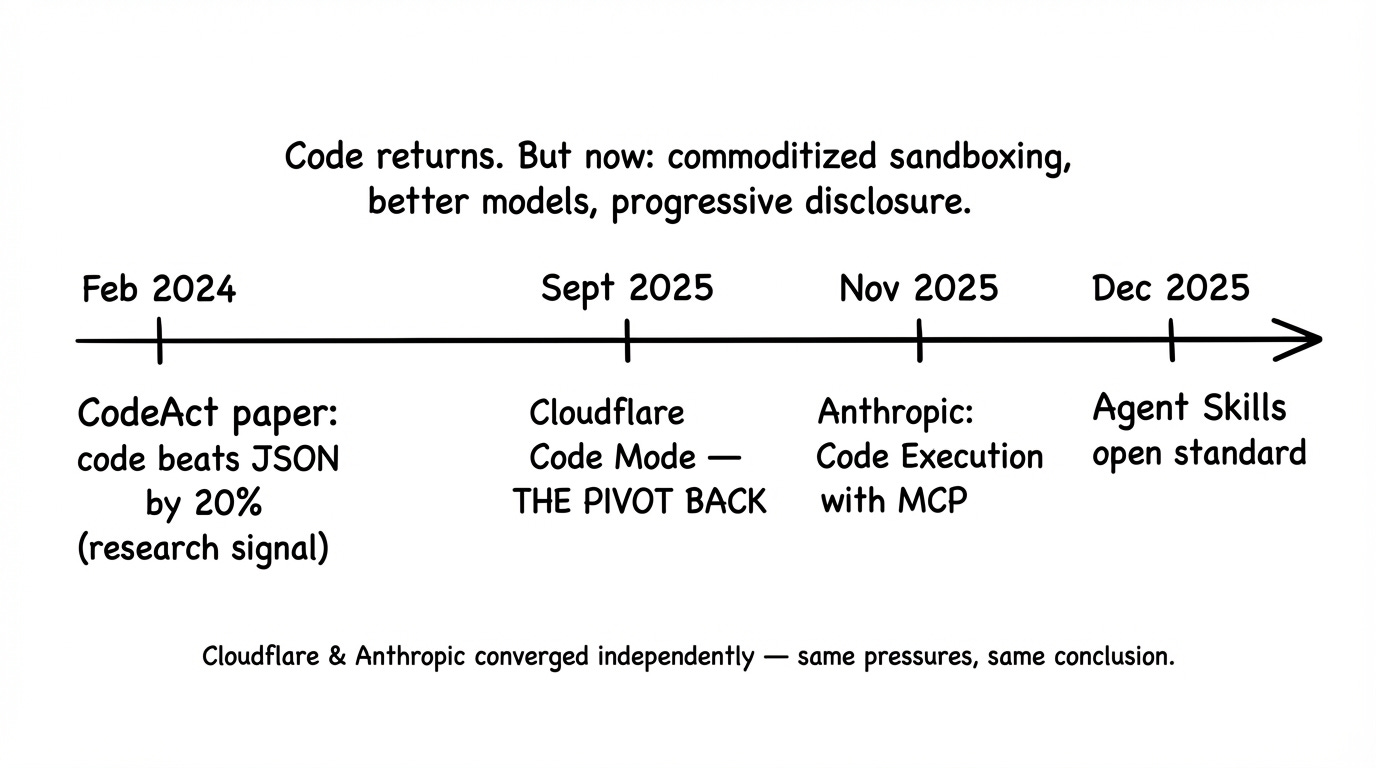

Then everyone moved to structured tool calling, driven by libraries like Instructor (from Jason Liu) and Pydantic that promised “guarantees about output types” with automatic validation and retries. Now it’s moving back to code (citing efficiency gains).

This post traces that arc and explains why the return may or may not make sense.

This post draws on themes from Designing Multi-Agent Systems, which covers tool design, code execution, and security considerations for agents in depth.

Era 1: Action via Code

At about mid 2022, OpenAI Davinci2 models were getting really good at writing code and it became clear that they could write code that got executed in a loop to solve problems. The setup was simple: prompt the model to write code in detectable blocks (triple backticks, XML tags), parse it out, execute it. This was attractive as it mostly worked across models of all sizes (for the longest time, most models just did not support json mode or structured tool calling, especially small 7B models that drove the bulk of experimentation at the time).

As an example, in the early days of AutoGen Studio, users could write a generate_image.py file with a generate_image() method. The model was prompted to write code that assumed those skills existed and could import them:

# AutoGen Studio skill file (2023)

# skills/generate_image.py

def generate_image(prompt: str, size: str = "1024x1024") -> str:

"""Generate an image using DALL-E and return the URL."""

# ... implementation

return image_url

The model didn’t call a tool; it wrote a program that orchestrated tools:

# Model-generated code

from skills import generate_image, save_to_disk

url = generate_image("a sunset over mountains")

save_to_disk(url, "sunset.png")

print(f"Saved image to sunset.png")

The problems:

Unreliable. You were dependent on the model following prompt instructions. Would it use the right code block format? Would it call the skill you defined or hallucinate something else?

Insecure. Models could write destructive code.

rm -rf, data exfiltration, anything code can do. This drove the race to support sandboxed environments - Docker, WASM, etc.High exposure. Code interpreters were general-purpose, which meant general-purpose attack surfaces especially with prompt injections still being a really serious issue at the time (most models had zero safety fine-tuning at the time). As Hugging Face’s smolagents documentation [2] puts it: “No local python sandbox can ever be completely secure.”

Era 2: Action via Tool Calling

Structured tool calling improved things. Instead of arbitrary code, you defined discrete tools with JSON schemas. A tool did one thing with typed inputs and outputs. The model selected tools and filled parameters - a constrained problem compared to open-ended code generation.

Benefits:

Reliability. Structured output became a solved problem. Models got good at producing valid JSON. Pydantic, Instructor and similar libraries formalized the patterns.

Security. No sandboxes needed for the tool layer. Either your

get_weather()function was secure or it wasn’t. You could audit tools independently. The blast radius was bounded.Clean abstraction. APIs and functions wrapped as tools felt natural.

One downside: this approach alienated smaller models. They couldn’t reliably produce structured output.

The tool use era was also driven by the introduction of MCP by Anthropic in November 2024 as an open standard for connecting AI assistants to external data systems. The core idea: write a tool once as an MCP server, and any client that supports the protocol can use it. MCP was designed to solve the “M×N problem” - if you have M AI applications and N tools, you’d otherwise need M×N integrations. MCP reduces this to M+N.

Era 3: Back to Code

Recently there’s been a pivot back to code-based action. Anthropic’s SKILLS approach is one example - folders containing a SKILL.md file plus scripts and resources that agents discover and load dynamically. Cloudflare’s Code Mode [4] converts MCP tools into TypeScript APIs that agents call via generated code. Anthropic also released an article citing efficiency gains from representing MCP tools as code that agents can compose.

What challenges are driving the code pivot?

Context explosion. Every tool call consumes tokens -the definition, the call, the result. Chain multiple tool calls and you burn through context on overhead. As Anthropic’s engineering team notes in their post on code execution with MCP [5]: “loading all tool definitions upfront and passing intermediate results through the context window slows down agents and increases costs.” Cloudflare’s benchmarks show code-based tool invocation can reduce token usage by 98.7%—from 150,000 tokens to 2,000 [4]. For long-horizon tasks, this becomes a real constraint.

Repetitive tool calling. Tool calling encourages sequential, atomic operations. Processing 100 items means 100 tool calls. The overhead compounds.

Restricted problem-solving. When the model can only compose tool calls (sequential or parallel), you’ve limited it to what you anticipated. Code allows complex control flow - loops, conditionals, error handling - to solve larger subproblems in one pass.

Vercel recently demonstrated an extreme version of this pattern [14]. They stripped their text-to-SQL agent from 15+ specialized tools down to two: bash execution and SQL execution. Instead of curated tool schemas, they gave Claude Opus 4.5 direct filesystem access to their semantic layer definitions. The claimed results: 3.5x faster execution, 100% success rate (up from 80%), and 37% fewer tokens. Their framing - “Model + file system + goal” - is radically simpler than orchestrating dozens of tools. However, the post notably omits how security is preserved. They mention “Vercel Sandbox” but never elaborate on isolation properties, prompt injection defenses, or what prevents destructive commands (perhaps they assume trusted users and correct queries from the slack users of the tool?). For anyone implementing similar patterns, these questions matter - you can only afford radical simplicity at the agent layer if you have tested, robust sandboxing underneath (a non-trivial requirement that often goes undiscussed). See the Agent Security Rule of Two framework below for one way to think about these trade-offs.

Early research signal also highlight code efficiency - Wang et al.’s CodeAct paper [6] (ICML 2024) showed that using Python code as the action format outperforms JSON-based tool calling by up to 20% in success rate across 17 LLMs tested. Code actions also required 30% fewer steps on average—which translates directly to lower token costs.

The reasons aren’t mysterious. Code has better composability (you can nest actions, define reusable functions), better expressiveness for control flow, and leverages the procedural knowledge already in the model’s pretraining data.

What Changed? Security and Infrastructure

The observant reader will notice: the security problems that pushed us away from code are still there. Models can still write insecure code. They can still be jailbroken (admittedly not as easily as before).

What’s changed:

1. Sandboxing infrastructure is now commoditized. Major providers now offer built-in code execution sandboxes. OpenAI’s Code Interpreter [10], Google’s Gemini Code Execution [11], Anthropic’s Code Execution Tool [12]. Developers flip a switch; the provider handles sandboxing. For custom solutions, gVisor and Docker are production-ready. Cloudflare’s V8 isolates launch in milliseconds [4]. Sandboxing went from “hard problem you solve yourself” to “managed infrastructure you consume.”

2. Models became less gullible (Safety Training). Significant safety training on code injection makes previous mistakes rarer. Models are better at refusing obviously malicious instructions (though dedicated adversaries can still cause problems).

3. Code is in the training data, tool calls aren’t. LLMs have seen enormous amounts of real-world TypeScript and Python in pretraining. They’ve seen far fewer examples of JSON tool-calling schemas. As Cloudflare notes [5]: code is a more natural action format for models trained on code compared to some esoteric function signature representing an MCP tool. LLMs are trained on GitHub. They are native speakers of Python/TypeScript. They are second-language speakers of your specific get_customer_data JSON schema.

4. Context preservation is now understood as critical. Research shows that LLMs struggle with large contexts even when they fit in the window. Anthropic’s context engineering guidance [8] treats the context window as “a precious resource to be managed” with techniques like compaction, structured note-taking, and multi-agent architectures. For long-horizon task solving, context efficiency matters.