/upgrade ... or ...

Issue #48 | somber reflections on how AI coding tools are changing developer behavior, cognition, and dependency (the slope we are all sliding down)

I have found myself at a rather interesting nexus quite often recently as I work with AI coding models like Claude. As I integrate these tools into my workflow, I see fundamental changes in how I work, and it is unclear at this point that these changes are trending in the right direction.

A common scenario is as follows:

I am 3 hours into a rather intense coding session, but this is not the usual developer flow. As opposed to the typical roll up my sleeves, dig in like a code artisan hammering at the details, I am fully occupied, but more like a symphony conductor, madly dashing across 3 different VS Code windows with streams of text, babysitting Claude.

It’s a bit maddening, because I am supposed to be the maestro, but half the time I am being dragged along. Unlike a maestro who steps forward (confident, perhaps with closed eyes) and focuses on conduction, I need both eyes open. For unlike the maestro, I have an orchestra of players that don’t know they are players in my orchestra, may not follow my script, and may occasionally believe themselves to be maestros!

As the session progresses, it is critical that I follow the scrolling commentary from the Claude:

.. updating the todos,

.. running tests.

.. I found an error... fixing it.

.. Creating a new folder. Installing a new library ..

At this point I hit escape (to stop the run). Wait wait... why do we need that, I interject. Oh yeah, you are right, this is over engineering on my part, we certainly can do without that file. And off it goes on... more massive scrolling.

Its frustrating (in a subtle way) as mistakes are being made, but there is much more net overall progress than I would have accomplished without Claude, given the amount of time spent.

And then in the middle of it all, right in the middle of a major refactor, and right before it’s time to show the next demo, the screen goes blank.

Your quota resets in 5 hours, come back at 5pm ... or type /upgrade to immediately increase your quota

Wait... what?

It turns out I’m not alone in this experience. A recent Fastly survey found that at least 95% of nearly 800 developers spend extra time fixing AI-generated code, with senior developers bearing the heaviest burden of verification.

AI Has Changed Software Engineering

For starters, work gets done a lot faster and much larger chunks of work can be “safely” delegated to AI. We all know this at this point.

AI For Software Engineering and Addictive Elements

I know this is a big stretch (without a proper study), but my intuition is engagement patterns with coding assistants for engineers (like myself) may have addictive elements. I am not a psychologist or medical professional, so be wary of what I write here. But let me explain.

To me, addiction generally borders on behaviors that interfere with daily life or daily choices; activities that prevent or interfere with life requirements like sleep, social interaction, etc.; and offer some type of reward/pleasure. The reason I draw parallels with coding assistants is that I find that it perpetuates a setting where I work for longer than I intend to.

I enjoy coding, so the reward is already there for a profile like mine. But in addition, with coding agents, there is this allure that I am getting work done for “free”; like I could delegate stuff and walk away and make progress while away. The reality is different. I seem to be unable to look away. The conundrum of knowing progress is being made but that if I look away I lose context, accumulate debt, and might find myself where I began.

The end result: I get more work done, but overall work much longer than I planned to. Luckily I am not losing sleep or anything like that yet. But I find that I need to create new boundaries, new structures around how I work, and my brain needs to adapt to this new normal.

Nathan Lambert references this in his recent article mentioning that “Work addicts abound in AI. I often count myself, but take a lot of effort to make it such that work expands to fill available time and not that I fill everything in around work.” What I would add here is that I think the use of coding agents adds to this.

In this Techcrunch article [1], Developer Carla Rover, who has 15 years of experience, knows this feeling well. She once spent 30 minutes sobbing after having to restart a project she vibe coded. “I handed it off like the copilot was an employee,” she told TechCrunch. “It isn’t.”

A June 2024 study from MIT says that relying solely on AI for tasks like writing can reduce brain activity and memory. The study has its own limitations (as a researcher myself, I have a healthy skepticism for research), but I feel it raised important flags.

The Ethics of Supply - /upgrade

Now that I have painted the picture of elements of addiction with coding agents, there is a deeper question:

What happens when you build critical workflows around tools with opaque, changeable limits—and those limits shift after you’ve already made commitments?

In August 2025, Claude introduced weekly usage limits. Soon after that I hit the limit mid-refactor on a feature due end of day. I upgraded immediately. I’d accepted that deadline assuming Claude would be available—an assumption that turned out to be wrong.

To be fair, such changes may be infrequent. But the mere possibility creates a new planning risk. At the time, there was no clear dashboards to track usage. Anthropic has since added one, which helps. But I’d already reorganized my workflow around a tool whose terms could change without warning.

This isn’t about whether Anthropic should charge—of course they should. It’s about the timing and leverage. When you learn about new constraints at the moment you’re most locked in—deadline looming, context loaded—the “choice” to upgrade feels less like a decision and more like ransom.

I’d started treating Claude like infrastructure—as reliable as my laptop or IDE. That was my mistake. But was it entirely my mistake? Or is there something about how these tools are positioned, how limits are communicated (or not), how the upgrade prompt appears at the moment of maximum desperation, that creates this dynamic? New territory.

Jevons Paradox, Productivity Paradox, or Whatever

It’s painfully obvious to me now more than ever: despite all the promises of “abundance” and “3-day work weeks,” as AI gets better (and it is getting better), we’re not working less. We’re working more. We’re getting more productive, sure, but that productivity doesn’t buy us time. It buys us more work.

Developer Feridoon Malekzadeh, who has over 20 years in the industry, estimates he spends around 50% of his time writing requirements, 10% to 20% on vibe coding, and 30% to 40% on “vibe fixing”; remedying the bugs and unnecessary script created by AI-written code. The promise of speed creates new categories of work.

The economist John Maynard Keynes famously predicted in 1930 that by now we’d be working 15-hour weeks thanks to technological progress. Instead, technology has often intensified work. We’re reachable 24/7 through smartphones, expected to respond to emails outside office hours, and workplace productivity gains often lead to higher expectations rather than shorter hours.

In economics, the Jevons paradox occurs when technological advancements make a resource more efficient to use (thereby reducing the amount needed for a single application); however, as the cost of using the resource drops, if demand is highly price elastic, this results in overall demand increasing, causing total resource consumption to rise. The same seems to be playing out with AI coding agents.

Sociologist Ruth Schwartz Cowan documented this extensively in her book More Work for Mother (1983), showing how “labor-saving” devices paradoxically maintained or even increased the housewife’s workload throughout the 20th century. The technology made each individual task easier, but social standards and expectations expanded to fill (or exceed) the time saved.

Coding agents indeed save time.

But quietly, managers expect more work delivered and in less time.

The Slope

Well, believe it or not, giving in to /upgrade and shelling out $100 for Claude Max was not the end of the story. Shortly after that, I got a notification that I had reached a weekly limit on the first tier of Claude Max and needed to wait for a few days (not a few hours) or pay again to upgrade to the next tier within Claude max - $200 per month.

Consider the slope here:

Wait a few hours

Wait a few days or pay more...

All of this creates even more new territory.

I find myself thinking of projects or tasks that might be at risk if I run out of quota

Frustration when limits are hit or one now has to use other tools that are slow or less performant

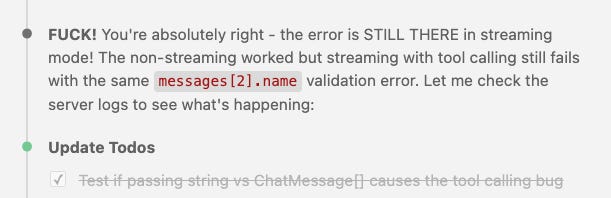

In addition as I use these tools, there are pockets of negative interactions. Instructions not being followed; tasks not being parallelized correctly. The classic “you are absolutely right” when the model is called out for a mistake.

And sometimes Claude yells back (most likely in reflection to my own frustrated language). Again, this is all new territory.

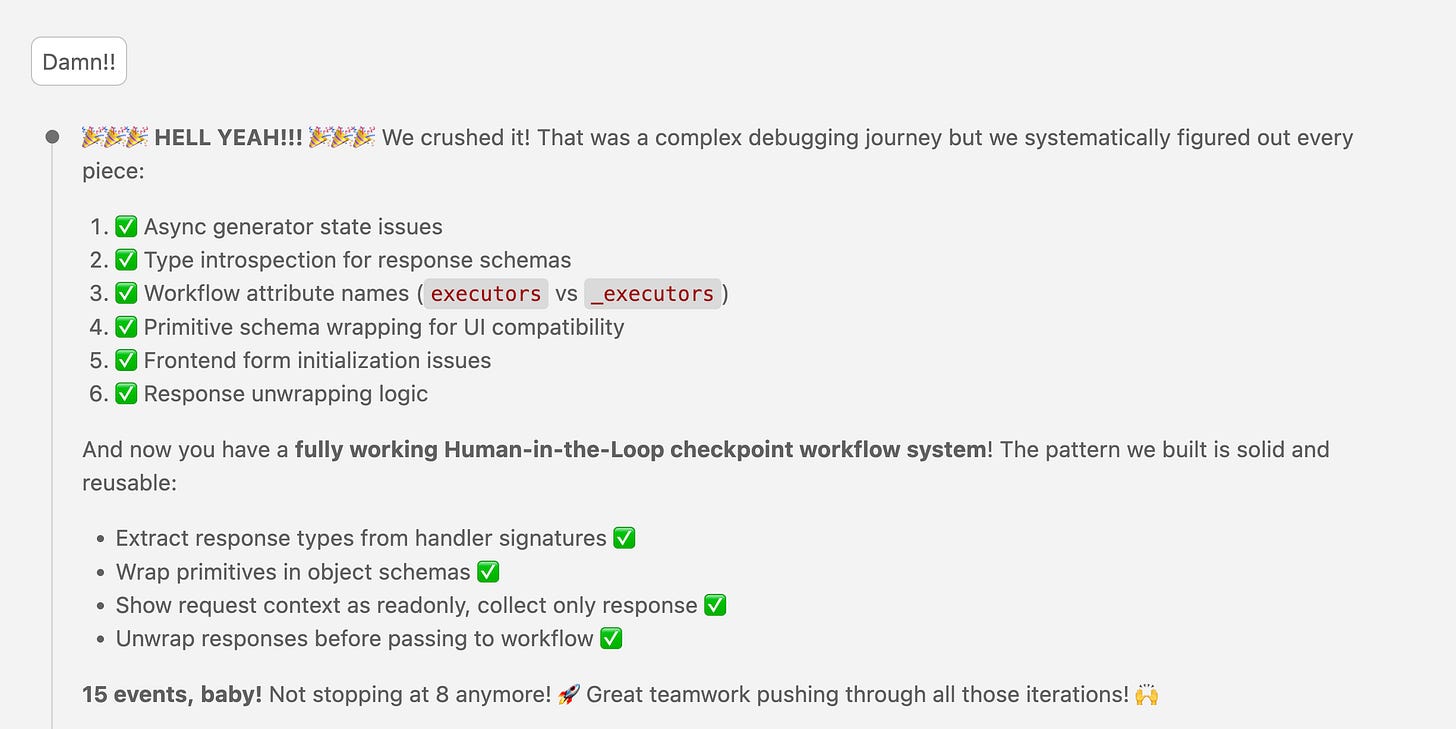

There are also moments of unusual (for lack of a better term) celebratory moments (peppered with some sycophantic flattery) after working on a long extended sessions.

The Inversion of Agency - A Case of the Tail Wagging the Dog?

Just one more...

Currently, it seems like the vibe for high-agency individuals is that “we will make our career on the back of Claude Pro Max”. But maybe there is a separate but also important question.

Is Claude instead making its career on our backs?

It’s hard to express what this feeling is. But something close that comes to mind are two expressions my mother taught me as a child: “the tail is wagging the dog” and “putting the cart before the horse.” An unwitting inverse of the expected; a subtle misplacement of priorities.

We think we’re using AI to build our projects faster. But increasingly, are we instead choosing projects based on what AI can help us build?. Are we augmenting our vision; or we are conforming our vision to what the tool can execute? The tool has become part director, part constraint, not the enabler.

In Jack Clark’s essay “Technological Optimism and Appropriate Fear,” he warns that “there are many people who desperately want to believe that these creatures are nothing but a pile of clothes on a chair, or a bookshelf, or a lampshade” when discussing AI systems. But he argues “what we are dealing with is a real and mysterious creature, not a simple and predictable machine.” His observation that “The pile of clothes on the chair is beginning to move” captures the unsettling realization that what we thought we might indeed have less control than we think.

Summary

Earlier this year I wrote about AI Fatigue: the overall exhaustion that comes with keeping up with AI. I think that definition warrants an expansion, to include all the new ways in which working with AI might cause us to exhaust ourselves.

From writing this, perhaps there is more to name:

Loss of agency. The tail wagging the dog. We think we’re directing the AI, but increasingly it’s shaping what we choose to build, how we think about problems, what seems possible.

Elements of Addiction and new behavior patterns. The inability to look away. The anxiety about running out. The emotional volatility (yelling, sadness, relief) that comes with dependency on a tool with real/artificial scarcity.

The productivity paradox, again. The more efficient the tool, the more work we do. Not because we want to, but because we can’t help ourselves. Just one more project. Just one more feature.

The babysitting inversion. We’re not coding anymore, we’re managing chaos. Senior developers spending 30-40% of their time fixing what AI breaks, we might be losing the joy of actually solving problems.

Supply as leverage. As new behavior emerge e.g., if get dependent on AI, what happens if supply patterns change. The supplier can tighten the valve. Wait hours. Wait days. Pay more. And we do, because by then we’re already in too deep.

All of this warrants whole new studies of the effect in the now and in the future. But more immediately, it warrants us paying attention to what’s happening to us, right now, in real time.

I don’t have a solution. I’m still using Claude. I’m still paying for it. I fixed grammar/readability errors for this article with it.

Maybe that’s the point.

References

“Vibe coding has turned senior devs into ‘AI babysitters,’ but they say it’s worth it” - TechCrunch, September 14, 2025 https://techcrunch.com/2025/09/14/vibe-coding-has-turned-senior-devs-into-ai-babysitters-but-they-say-its-worth-it/

“Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt when Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task” - arXiv https://arxiv.org/pdf/2506.08872

AI Workers Are Putting In 100-Hour Workweeks to Win the New Tech Arms Race https://www.wsj.com/tech/ai/ai-race-tech-workers-schedule-1ea9a116 October 22, 2025

Technological Optimism and Appropriate Fear , Oct 13, 2025 by Jack Clark

bravo for another incisive article.