Is Scaling a Dead End? Why Model Scaling is Necessary Infrastructure

The bitter lesson isn’t dying. It’s being amortized.

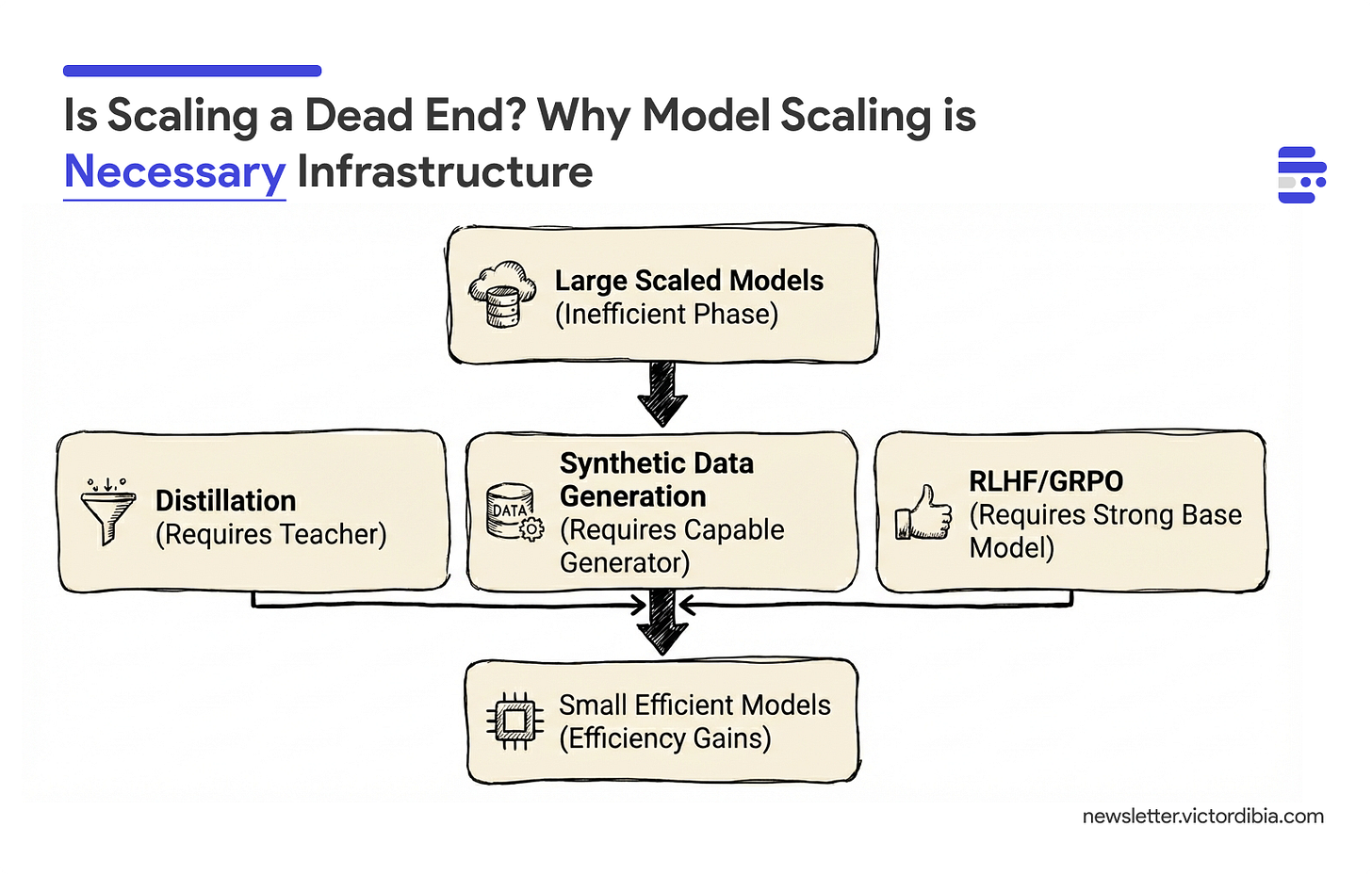

TLDR; It’s true - direct scaling is showing signs of diminishing returns. However, a missing part of the debate is that massive scale is perhaps unavoidable. Rather, large base models are the critical infrastructure required to distill, train, and validate the efficient small models (or alternate architectures) of the future. In other words, efficiency gains we see today, including distillation, synthetic data, RLHF, and GRPO, are not alternatives to scaling. They are dividends from the scaling investments that preceded them.

As investments in AI explode (Big Tech expected to spend 300 Billion on AI in 2025), data centers are built, and most industry labs seem entrenched in the view that more GPUs is better, there is a natural question: is the quest to throw compute at the problem valid? Or better still, should it be the only approach?

There seem to be two camps. On one side are folks who agree that scaling has got us this far when nothing else did, and will likely be the gift that keeps on giving. A faction of the bitter lesson believers [1]. On the other are those who argue it’s a dead end, either due to the clear unsustainability of it all, or because there are fundamental flaws in the current transformer architecture itself that mean we can’t get much farther than we are today. This second camp often points to new approaches, such as world models and alternative architectures, as the path forward, or point to emerging cracks or instability in the scaling laws.

As I think about both, I am left with the idea that there is some nuance that is worth clarifying. We probably should not try to scale ad infinitum, but at the same time, scale is unavoidable in that its more of a design feature than a bug.

On the Slow Death of Scaling (By Sara Hooker)

This post is in part a reflection inspired by Sara Hooker’s essay, On Slow Death of Scaling [2], where she argues that recent developments show cracks in the scaling laws that have enabled progress thus far, and that it is time to invest in other areas to extract performance gains: data quality, improvements in system scaffolding (agents), and a focus on UX. The reasons cited include diminishing returns on scaling, unreliable scaling laws, and the availability of surgical synthetic data generation for training smaller, higher-quality models.

One of the arguments Sara makes on the unreliability of scaling laws is that they predict test loss, not downstream capabilities. When you measure what models actually do, the scaling law predictions sometimes break down, which means companies betting everything on scale are probably under-investing elsewhere.

I agree with everything Sara says here (she’s great and definitely read more of her writing).

However, the minor challenge I see is that a reader of that article might walk away thinking we probably do not need the super-scaled models. I think we critically and necessarily do. And that there is a cyclic, chicken-and-egg dependency between the super-scaled models (for lack of a better term) and all of the innovations that help us move away from them.

In plain terms: small models are a derivative of the larger models, and probably will never be better than them. This follows a well-established engineering pattern.

Downstream of Scale: Why Efficient Models Require Large Ones

Several observations point to the constant need for super-scaled models - and how they are (IMO) necessary infrastructure for progress.

Smaller Models Are Distilled from Larger Ones

Knowledge distillation, training smaller “student” models to mimic larger “teacher” models, has become a cornerstone of efficient AI deployment. But the technique has an obvious dependency: you need the teacher first. Even when the goal is to just improve performance (e.g., reasoning models), you still need strong, capable base models.

DeepSeek’s work on distilling reasoning capabilities validated this directly: “reasoning patterns of larger models can be distilled into smaller models, resulting in better performance compared to reasoning patterns discovered through RL on small models” [3]. The implication is clear. You cannot bootstrap reasoning in small models without first having large models that possess it.

Synthetic Data Is Generated by Large Super-Scaled Models

The synthetic data revolution, which enables training smaller, specialized models on carefully curated generated data, depends entirely on capable generators. Research on self-improvement methods shows that when models generate their own training data, they are “only limited by the best model available” [4]. This creates a ceiling: your synthetic data is only as good as your largest model.

The industry pattern is consistent. NVIDIA’s Nemotron-4 340B, IBM’s LAB methodology, and Mixtral-8x7B all use large teacher models as the source for synthetic training data. The small, efficient models that result are derivatives of the large ones that generated their training signal.

Advances Like RLHF and GRPO Require Strong Base Models

Reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) and techniques like Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) have dramatically improved model capabilities. But these techniques are refinements, not foundations.

As Nathan Lambert notes in The RLHF Book: “Effective RLHF requires a strong starting point, so RLHF cannot be a solution to every problem alone” [5]. OpenAI’s research on weak-to-strong generalization found that “weak-to-strong generalization is particularly poor for ChatGPT reward modeling... naive RLHF will likely scale poorly to superhuman models without additional work” [6].

GRPO, which enabled DeepSeek-R1’s impressive reasoning capabilities, works by sampling multiple completions and using group-relative rewards. But this requires a base model strong enough that variance exists in sample quality and some samples actually reach correct answers. DeepSeek-R1-Zero, often cited as evidence that pure RL can discover reasoning, started from DeepSeek-V3-Base, a 671-billion parameter model [3, 7]. The “pure RL without supervised fine-tuning” innovation was only possible because they had already paid the massive scaling tax.

The Dependency Graph

The relationship looks something like this:

Large Scaled Models (the "inefficient" phase)

↓

├──> Distillation (requires teacher)

├──> Synthetic Data Generation (requires capable generator)

└──> RLHF/GRPO (requires strong base model)

↓

Small Efficient Models (the efficiency gains we celebrate)

Every technique in the middle layer requires capable large models as input. Small efficient models cannot bootstrap themselves.

Even “Alternative” Architectures Follow This Pattern

One might hope that fundamentally different architectures, such as world models and JEPA, could escape this dependency. The evidence suggests otherwise.

Yann LeCun has been vocal that autoregressive language models and scaling obsession are the wrong path to advanced AI. He argues that “simply scaling the model and providing it with more data might not be a viable solution” and proposes JEPA (Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture) as an alternative focused on learning world models [8].

Yet Meta’s own V-JEPA 2 paper tells a different story. The model scales from 300 million to over 1 billion parameters, trained on more than 1 million hours of internet video [9]. The paper explicitly identifies scaling as a core ingredient: data scaling (2M to 22M videos), model scaling (300M to 1B+ parameters), and longer training (90K to 252K iterations). Most tellingly, they report that “V-JEPA 2 demonstrates a linear scaling behavior with respect to model size.”

Google’s Genie world models follow the same trajectory. Genie 2, their foundation world model, “demonstrates various emergent capabilities at scale, such as object interactions, complex character animation, physics, and the ability to model and thus predict the behavior of other agents” [10]. Google’s job postings for the team state plainly: “We believe scaling [AI training] on video and multimodal data is on the critical path to artificial general intelligence” [11].

The architecture changes. The scaling dependency doesn’t. Or maynot.

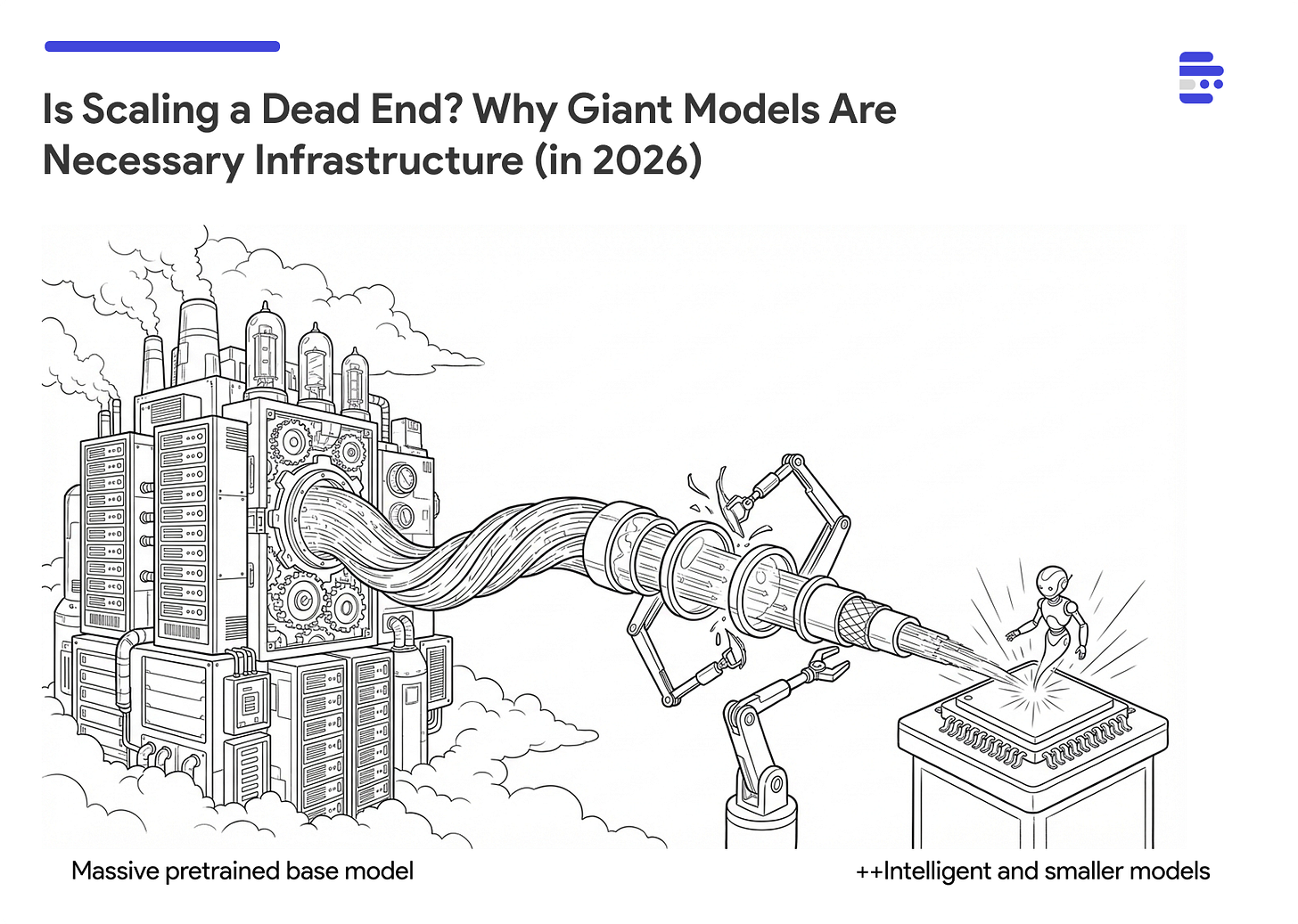

The Engineering Pattern

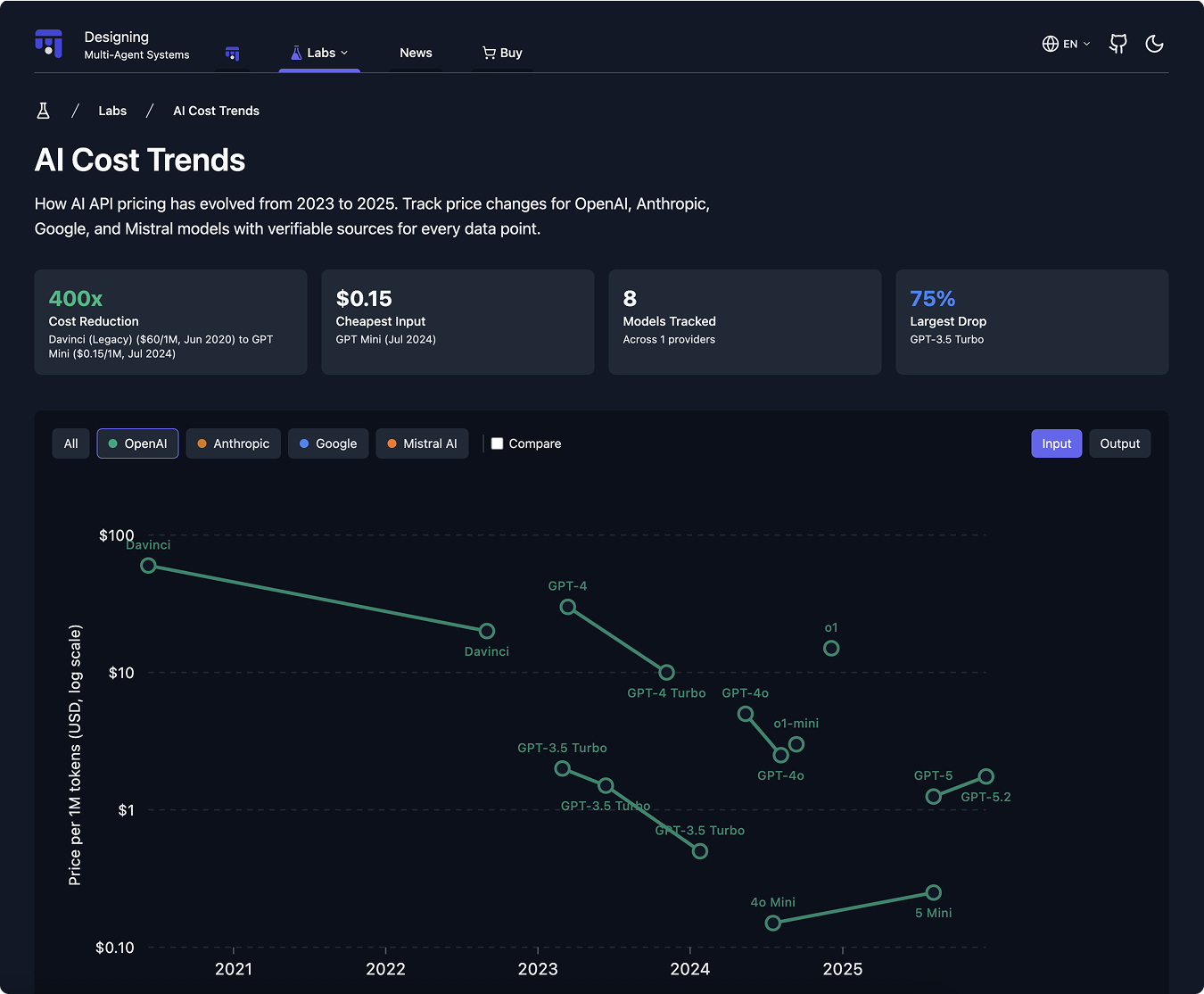

Personally, I think this is how OpenAI has been able to improve both performance and cost over the last several years (caveat, this is speculative), by amortizing their scaling investments across increasingly efficient derivative models. It may be unclear to most, but the price of the best quality intelligence has dropped 400x in the last 4 years. Let that sink in.

This follows an engineering pattern we see across industries. You build the big, expensive, “inefficient” version first, with clear intent, and then do the work to make it small. Early CPUs were room-sized; now they fit in your pocket. Early aircraft were massive and inefficient; optimization came later. The brute-force version comes first, optimization follows.

What’s unique about ML is that the brute-force version doesn’t become necessarily obsolete in the near term. It remains operationally necessary as infrastructure for producing the optimized versions.

Conclusion

The efficiency gains we see today, including distillation, synthetic data, RLHF, and GRPO, are not alternatives to scaling. They are dividends from the scaling investments that preceded them.

It is unclear that even new architectures will allow us to escape this cycle. Even with the promise of world models, they appear to follow this arc as well. And maybe that’s fine. What might be needed is a commitment to the shrinking pattern that most industries are accustomed to: build the big version (with clear intent), then do the work to make it small.

The bitter lesson isn’t dying. It’s being amortized.

References

[1] Sutton, R. (2019). The bitter lesson. Incomplete Ideas. http://www.incompleteideas.net/IncIdeas/BitterLesson.html

[2] Hooker, S. (2024). On the Slow Death of Scaling. arXiv preprint. https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.05694

[3] DeepSeek-AI. (2025). DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in LLMs via reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint. https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.12948

[4] Alemohammad, S., et al. (2024). Self-consuming generative models go MAD. ICLR 2024. https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.01850

[5] Lambert, N. (2024). The RLHF Book. https://rlhfbook.com/

[6] Burns, C., et al. (2023). Weak-to-strong generalization: Eliciting strong capabilities with weak supervision. OpenAI Research. https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.09390

[7] DeepSeek-AI. (2024). DeepSeek-V3 technical report. arXiv preprint. https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.19437

[8] LeCun, Y. (2022). A path towards autonomous machine intelligence. OpenReview. https://openreview.net/pdf?id=BZ5a1r-kVsf

[9] Bardes, A., et al. (2025). V-JEPA 2: Self-supervised video models enable understanding, prediction and planning. arXiv preprint. https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.09985

[10] Google DeepMind. (2024). Genie 2: A large-scale foundation world model. DeepMind Blog. https://deepmind.google/discover/blog/genie-2-a-large-scale-foundation-world-model/

[11] Kostrikov, I. (2025, January 6). Google is forming a new team to build AI that can simulate the physical world. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2025/01/06/google-is-forming-a-new-team-to-build-ai-that-can-simulate-the-physical-world/